A DIFFERENT PERCENTILE

Tap the photo above to view an Episode of:

Recovery Uncut

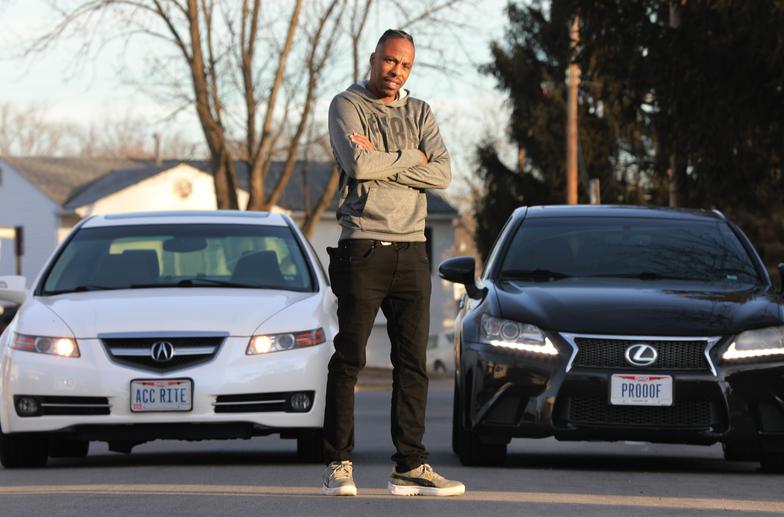

Lee Burge was charged with murder and served 16 years in prison after he shot and killed his friend in 1993. Now he said he gives back by working in the drug and alcohol recovery industry.

Doral Chenoweth III | Columbus Dispatch

At 45 years old, Lee A. Burge appears to have an idyllic life.

He’s married with two kids and a dog, and they live in a white, suburban house on the South Side.

A motivational speaker, he has built a fulfilling career in the drug and alcohol recovery industry, working for KAV Health Group, an agency on the North Side, and at a residential rehab facility in Minerva Park.

And each day, he makes sure he parks his two cars the same way in his garage so he can read the vanity plates in order:

“ACC RITE” and “PROOOF” — a reminder that living an upstanding life yields positive results.

He said people often count his accomplishments and take in his bright smile, charming demeanor and natty attire — often punctuated by a bow tie — and compliment him. “You’re doing good,” they say. Or they marvel at his ability to juggle so much responsibility. “How do you keep going?” they ask.

“I tell them, ‘I owe,’” Burge said. “I owe because I took a life. I feel like every day I have to do enough good for two people.”

More than 25 years ago, on Sept. 24, 1993, Burge shot and killed his friend, Michael Early, at an apartment complex in Dayton.

“I can remember it was cool,” said Burge, who was 19 at the time. “I can remember standing in the housing complex. I can remember it just happening suddenly.”

According to Burge, a drug dealer at the time, Early was addicted to crack-cocaine and attempting to rob him. Burge said he pulled his weapon when he thought he saw Early reaching for a gun. (Authorities never found one, according to reports.)

Prosecution witnesses said that Burge and Early got into an argument before Early punched Burge and the shooting took place, according to trial coverage in the Dayton Daily News.

“Five shots later, I’m standing there and I’m looking down at someone that I care for,” Burge said. “I remember running away from the scene and just thinking, ‘This is bad. This is bad.’ … I went on the run for like two days and I couldn’t do anything but get high. I smoked weed, I drank because I couldn’t get the images out of my head.”

Burge turned himself in at a local TV station and was eventually charged with murder. He served more than 16 years in prison at multiple facilities, including Pickaway Correctional Institution in Scioto Township, before being paroled in 2010.

“

“I owe because I took a life. I feel like every day I have to do enough good for two people.”

Burge said that Early’s death and his own subsequent incarceration impacted him in three ways: It helped him abandon a life of crime. It prompted him to examine his own substance abuse and place in a cycle of addiction that included his mother, also an addict. And it motivated him to help others stay clean.

“I strive every day to be able to do for someone what no one could do for my mother or for [Early],” he said.

Born in a low-income area in Dayton, Burge grew up in challenging circumstances. His mother told him that his father was murdered, and because she struggled with addiction, Burge grew up in foster care.

There he looked up to older boys and their friends, including Early, who were caught up in a culture of dysfunction. Following their lead, Burge said he began selling marijuana at 12, crack cocaine at 14 and powder cocaine at 16.

“If somebody didn’t get beat, shot (or) we didn’t run from the police and get away, it wasn’t fun,” Burge said. “That was the mentality of the culture. … I can recall (the older boys) coming in with knife wounds and head wounds and one of our mottos used to be, ‘Did you die?’ And if you didn’t die, laugh about it.”

Burge almost made it out. He said he passed a GED test and received college scholarships based on his academic performance and personal circumstances. He enrolled at the University of Cincinnati with plans to study child psychology and political science.

But he dropped out less than a year later.

“I can remember sitting in my dorm room and cutting up bars of soap as if it was dope because that mentality was so ingrained in me,” he said. “I couldn’t do anything but mess it up.”

Each morning, he’d wake up and smoke marijuana as an escape from his life as a drug dealer.

“You have to be numb,” he said. “Just think about it; if you’re selling to somebody’s mother, you’re becoming the person that you hate.”

Lee Burge customized the license plates of his two cars to read “ACC RITE” and “PROOOF” as a reminder to live right.

Burge said it took him five years to understand the magnitude of taking Early’s life. He felt he’d become like someone else he hated — the person who’d killed his father. He said the realization came to him when he stepped on an insect in the prison yard.

“It broke me,” he said. “But I’m grateful for the breaking because that’s what allowed me to actually be able to rebuild.”

At Pickaway Correctional, Burge completed the OASIS therapeutic program for offenders with substance abuse issues. Afterward, he served as office assistant, reporting to then-director Anthony Ralph, who became his mentor.

Ralph, now a regional administrator for the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, said an important part of the recovery process is helping people reach a point of self-forgiveness. He described Burge as a “good-hearted guy” who appears to be in a healthy place.

“I can see it in how he treats others, how patient he is with (them), how he uses his de-escalation skills when there’s an issue, and he doesn’t lose his cool,” Ralph said. “You can see that he’s trying to pay a penance for what he has done.”

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it’s needed most. Subscribe today.

Subscribe to The Columbus Dispatch.

Burge met his wife, Tameka, 37, shortly after leaving prison in 2010. She watched him progress from working a job at a payday loan company to becoming a housing specialist at a drug-treatment facility, and eventually helping to start another agency.

She said Burge’s former clients often stop her in the street to talk about how much he has helped them.

“Before I met Lee, I was judgmental because that’s how I was raised,” she said. “You can’t take peoples’ lives; that’s in the Bible. … But Lee makes me believe that people can turn their life around.”

Burge said God has guided him on his career path. In addition to running KAV Health Group, he self-published a motivational book “The 13th Step” and provides recovery programs and other resources for people struggling with addiction under his brand, A Different Percentile.

Burge said he works at least 12 hours each day, and his phone constantly rings with calls from clients. He takes each one, said his wife, who, along with Burge, admits he struggles with balancing his job and family.

“I owe, but at the same time, how much do you owe and how long is the debt owed?” Burge said.

The answer is open-ended. Burge thinks of Early as a martyr, and likens him to an organ donor, giving Burge new life to keep giving back.

“I don’t have a right to not get up at 6 a.m. and go to work,” Burge said. “I don’t have a right to not help others. … I have a responsibility and no matter what, I will fulfill it.”

MAN DEDICATES HIS LIFE TO HELPING OTHERS AFTER TAKING FRIEND’S LIFE

After taking the life of a friend, the South Side resident served over 16 years in prison. Now working in the drug and alcohol recovery industry as a consultant with CRN, KAV and Minerva Park Behavioral Health; he strives to “do enough good for two people” each day. " I consider it a pleasure to work with great and qualified individuals; that care about saving the lives of other human-beings".

Erica Thompson The Columbus Dispatch

ethompson@dispatch.com http://www.twitter.com/miss_ethompson

Photos By:

Doral Chenoweth III | Columbus Dispatch

Video by Doral Chenoweth III.

Click the photo to the left; in order to read the stories of the others featured in this "powerful journal of pain, suffering and some triumph!"